The Genki Ala Wai Project

Students, Teachers, and the Community Working Together

Join us for a free community Genki Ball making and throwing event held every first Saturday of the month at the Waikīkī-Kapahulu Public Library!

January Community Event:

Saturday, Feb 7, 2026

@Jefferson Elementary School Wai Nani Way Entrance

1st session 9:00 am - 10:30 am

Collaboration, Not Controversy: The Real Story of Genki Balls and the Ala Wai

Response to Civil Beat Article: “Hawai‘i Loves ‘Genki Balls’ To Clean Water. New Studies Say They Don’t Work”

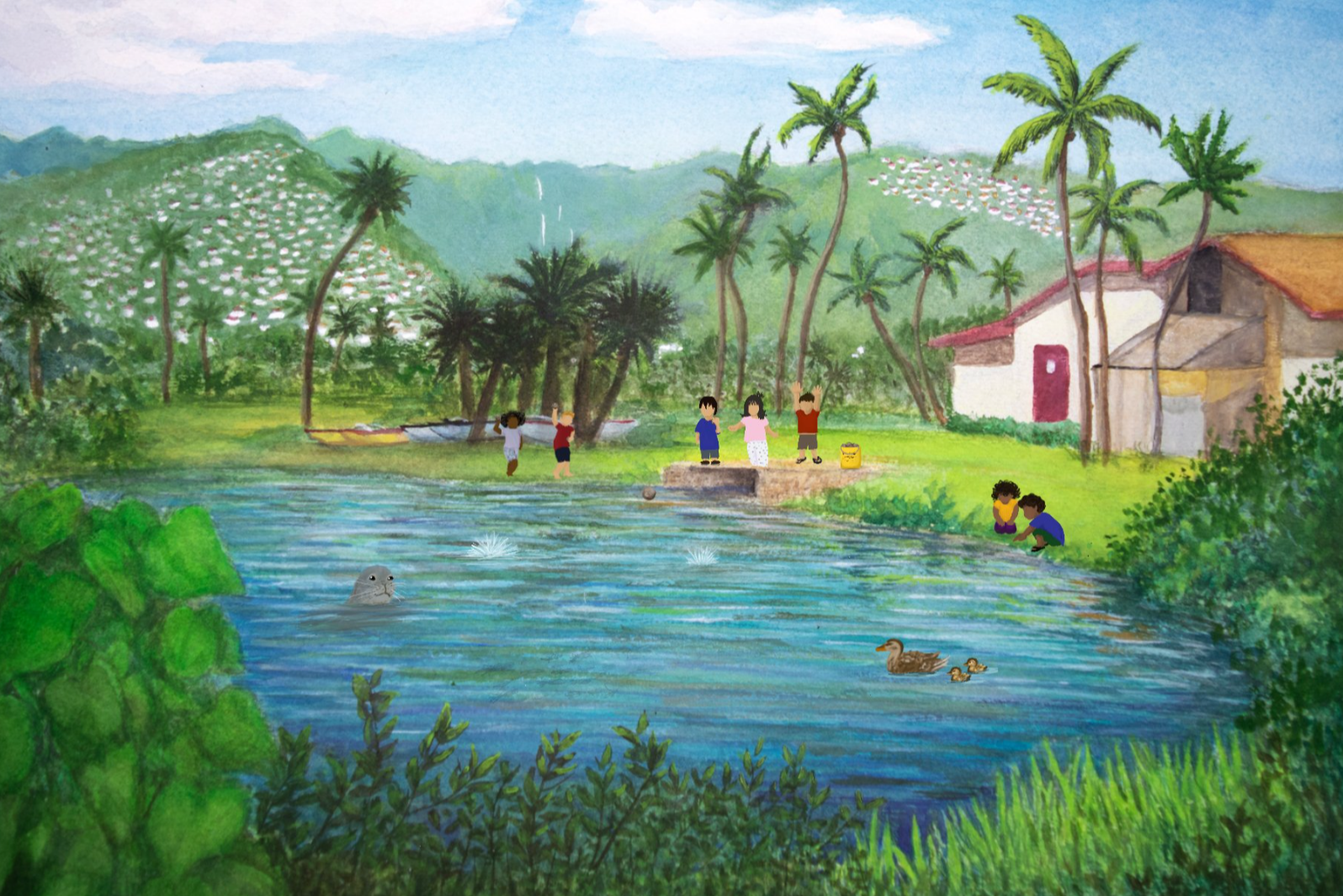

The Genki Ala Wai Project began with a simple idea: that ordinary citizens, acting together, can make a difference in restoring the Ala Wai Canal.

Since 2019, more than 17,000 volunteers from over 300 schools, businesses, and community groups combined have joined us to make over 270,000 Genki Balls, all without any government funding. Every step of this effort has been powered by donations and volunteer energy. Together, we have seen tangible progress: over 20 inches of polluted sludge reduced, cleaner water with far fewer Enterococci bacteria (a key indicator of sewage pollution) near the Hawaii Convention Center, and the return of marine life to areas where it had long disappeared. Today, sightings of native fish, hammerhead sharks, spotted eagle rays, and even monk seals are beginning to change the reputation of one of Hawaii's most polluted waterways.

Three months ago, Civil Beat published an article titled “Hawai‘i Loves ‘Genki Balls’ To Clean Water. New Studies Say They Don’t Work.” The headline was based on a tank experiment conducted by researchers at Hawaii Pacific University (HPU) in Hamakua Marsh. The researchers suggested that Genki Balls not only failed to improve water quality but actually worsened it.

While we respect their effort to study Genki Balls and Effective Microorganisms® (EM®), we want to clarify that the experiment does not represent the Ala Wai Canal or the decades of successful EM use and studies in more than 100 countries over the past 40 years. One of the most encouraging data points comes from the Surfrider Foundation's Blue Water Task Force site near the mouth of the canal. In 2020, only 44 percent of water samples met Department of Health safety standards for Enterococci. As of late 2025, that figure has increased to 74 percent over the past 12 months, reflecting the combined impact of community action, EM treatment, and greater public awareness of pollution sources.

We are a volunteer-based initiative focused on collaboration and education. However, since the article’s publication, participation in our free monthly community events has dropped by more than 70 percent. This misunderstanding has hurt a movement built on stewardship, and community pride. We feel a responsibility to clarify key points where the study and subsequent reporting may have created confusion.

Concerns with Conclusions of the HPU Study

1. Incomplete microbial analysis

The study measured bacterial community composition using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. However, this method does not capture yeasts and fungi, which make up one of the three major microbial groups in EM formulations (lactic acid bacteria, photosynthetic bacteria, and yeasts). Yeasts and fungi play essential roles in nutrient cycling, organic matter breakdown, and microbial community balance. These organisms are typically analyzed through ITS or 18S sequencing, which the HPU study did not perform. As a result, the findings represent only a portion of EM’s full microbial function.

2. Misinterpretation of EM’s ecological role

EM microorganisms act as catalysts, not as dominant species. Their purpose is to activate and rebalance native microbes, not to replace them. Measuring EM “dominance” rather than its biological activity overlooks how EM functions in nature and supports natural ecosystems.

3. Limitations to tank setup

The tanks used an equal ratio of sludge to water, which does not reflect the real conditions in the Hamakua Canal, where water depth reaches about eight feet and sediment is much thinner. And as with most tank studies, they can offer insights, but they cannot fully mirror the complexity of natural waterways.

What this means

After the study and the media coverage that followed, we requested a private meeting with the HPU researchers to share this scientific context and to explore collaboration. The university declined to meet until after publishing the completed study at Hamakua Marsh, which used only 200 Genki Balls over the course of two years. By comparison, the Genki Ala Wai Project has deployed over 270,000 balls over the course of six years, with as many as 5,000 Genki Balls on a single day. An experiment using only 200 Genki Balls could not demonstrate the cumulative or long-term effects of EM technology, which depend on continuous application and natural activation.

Our team has invested more than $50,000 in independent, third-party water testing in the Ala Wai to fulfill the parameters set by the DOH (Department of Health), and has made the results publicly available on our website (download link). We also shared expert input from Dr. Gustavo Pinoargote, microbiologist and President of EMRO USA, with HPU and Civil Beat. Pinoargote’s professional comments identified specific gaps in the HPU study’s methods and interpretation. Unfortunately, those insights were not included in the Civil Beat article. Including them could have helped the public better understand how EM technology works and prevented much of the confusion that followed.

We respectfully invite Civil Beat to consider a follow-up article focused on the scientific facts and the shared goal we all hold—to better understand what truly helps restore Hawaii's waters. We also extend our offer to provide Genki Balls for more comprehensive, collaborative testing to determine whether EM can contribute to restoring the ecosystem in Hamakua Marsh.

Moving Forward

In 2019, we began with six volunteers making mud balls with students from Jefferson and Ala Wai Elementary Schools. Soon local businesses and community groups joined in. Today, more than 4,000 visitors from overseas have helped clean our canal. What began as a small act of stewardship has grown into a community movement. This is not our project; it is everyone’s project.

The Genki Ala Wai Project reflects the spirit of aloha and kuleana, a shared responsibility to care for the places we love. It gives people a way to take part in protecting our environment. We are proud that the project is 100 percent donation-driven, supported entirely by residents, local sponsors, and friends from around the world.

We are also the first to acknowledge that Genki Balls are not a cure-all. They are designed primarily to reduce sludge and restore microbial balance. After 270,000 balls, we now see sand where there was once thick sludge, and the unpleasant odor has diminished. Broader problems such as runoff, pollutants, and trash require coordinated action throughout the entire ahupua‘a. Cleaning the Ala Wai is not only an environmental challenge but a broader socio-economic challenge that connects issues such as stormwater management and houselessness.

A Call for Collaboration

We invite families, schools, scientists, businesses, and community members to join us at our free community event on the first Saturday of each month at Kapahulu Library Lawn. Together, we make Genki Balls, learn about our watershed, and take collective action to restore our waterways.

We are also seeking research partners to help monitor and analyze water quality. Our hope is to collaborate with local laboratories and universities to identify pollution sources and create strategies for long-term restoration. We would also appreciate others sharing any existing Ala Wai data to help us build a more complete public database. We welcome participation from HPU researchers and scientists throughout Hawaii who share the same goals.

If you have attended an event or live near the Ala Wai and have noticed changes in smell, water clarity, or marine life, please write to us at genkialawai@gmail.com. Your observations help us document progress and inspire others to get involved.

Finally, we are waiting for the renewal of our Department of Health permit to apply the liquid form of EM solution into the Ala Wai. This method, used successfully in many parts of the world, works like probiotics for the ocean, helping restore natural microbial balance. We hope to begin once the permit is renewed.

From Division to Collaboration

From division, we choose collaboration. From debate, we choose dialogue. Science grows stronger through openness, transparency, and shared purpose, not through division.

Nicholas Carrillo, a fourth grader at Mililani Ike Elementary School and our youngest member who serves as the MC at our community events, reminds us: “The Ala Wai belongs to the marine life who call it home, the fish, the turtles, the monk seals, and the coral that thrive downstream in Waikiki and Ala Moana. We clean the canal not only for ourselves, but for them.”

Join us at our next community event on Saturday, December 6, and be part of this growing movement to make the Ala Wai clean and swimmable again in our lifetime.

Genki Hou!

The Genki Ala Wai Project Team

RELATED LINKS & REFERENCES

Civil Beat Article:

https://www.civilbeat.org/2025/09/hawaii-genki-balls-clean-water-new-studies-dont-work/

HPU Tank Study:

• Poster 1:

https://virtual.oxfordabstracts.com/event/44438/poster-gallery/grid?fullScreen=false¤t=319

• Poster 2:

https://virtual.oxfordabstracts.com/event/44438/poster-gallery/grid?fullScreen=false¤t=300

Expert Review — Dr. Gustavo Pinoargote (EMRO USA):

https://www.genkialawai.org/

Academic Report on Effective Microorganisms (EM):

https://emrojapan.com/treatise/

Response to Hawai‘i Pacific University’s Study in Hāmākua Marsh

Dr. Gustavo Pinoargote

President, EMRO USA, Inc

Methodological Considerations in Microbial Detection

The study relied exclusively on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. While this is a standard approach for bacterial community profiling, it measures relative abundance rather than absolute activity, and does not account for other microbial groups such as fungi. The study also restricted “EM” to a short list of strains, and interpreted the absence of these strains in high relative abundance as a failure of EM. This overlooks EM’s intended ecological role, which is not to dominate or permanently colonize ecosystems, but rather to stimulate and rebalance native microbial communities by altering conditions such as pH, metabolite production, and redox states.

Ecological Interpretation of Relative Abundance

Interpreting EM effectiveness through dominance in sequencing data reflects a limited ecological view. Rare taxa can play critical functional roles, and microbial consortia such as EM are designed to act as catalysts: encouraging the growth of beneficial native microbes rather than displacing them. A decline in relative abundance after initial deployment is not necessarily failure, but instead aligns with EM’s intended role as a temporary stimulus that supports ecosystems in restoring their own balance.

Scale and Context of Experimental Design

Small-scale tank experiments can be informative as initial models of microbial interaction. However, they cannot fully capture the dynamics of natural wetland systems, which are shaped by hydrological flows, sediment chemistry, light cycles, plant interactions, and wildlife activity. These complexities are difficult to replicate in static tank conditions. For this reason, tank experiments are most appropriate as hypothesis-generating tools, and conclusions about field-scale effectiveness should be tempered with recognition of these limitations and the need for in-situ monitoring.

Framing and Language of Findings

Several conclusions in the paper were framed in absolute terms, such as stating that “no EM persisted” or that “Genki Balls are not a good deployment method,” without acknowledging detection limits or ecological complexity. Similarly, labeling entire genera as “pathogens” without supporting assays risks overgeneralization, as most genera (for example Bacillus, Streptomyces) contain both beneficial and opportunistic species. A more neutral framing would have been to describe observed shifts in community composition while noting uncertainties and methodological constraints.

Alignment Between Results and Conclusions

Interestingly, the study's own results showed that EM-associated microbes did appear transiently in both sediment and water, at times peaking at up to 17 percent. Rather than being evidence of failure, this pattern is consistent with EM's ecological function as a catalyst. Temporary establishment followed by decline reflects its role in promoting system resilience rather than persisting as a dominant population. Acknowledging this nuance would provide a more balanced interpretation of the findings.

Our Goal:

To deploy 300,000 Genki Balls and use Effective Microorganisms® (EM®) bioremediation technology to restore the Ala Wai Canal’s ecosystem by 2026, making it safe for fishing and swimming again. We hope that the success of this project will inspire the cleanup of other polluted waterways on the island.

Our Mission:

To empower students, teachers, and the community to work together to restore the ecosystem in the Ala Wai Canal.

Mahalo to our amazing partners!